The Zen of Trading: Balancing Stubbornness and Flexibility

I recently read the iconoclastic psychiatrist Mark Epstein’s book The Zen of Therapy and it had an enormous influence on me. Epstein’s professional project has been to synthesize Buddhism with Western Psychology and it is an extraordinary success in my opinion. Just as there is a Zen of Therapy, there is a Zen of Trading.

Before getting into the application to trading, I want to introduce two crucial psychological concepts from Epstein’s work. The first relates to Buddhism. Most people are so firmly identified with their habitual thought, emotional and behavioral patterns that they are essentially living unconsciously.

According to Epstein, Buddhism counsels gaining some psychological distance from these impulses that drive us in order to give us an opportunity to consider their utility and opening up space for new, more evolved, responses. This is a tremendously powerful idea in my opinion.

The second relates to the work of the psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicot, who has had a big influence on Epstein. Winnicot’s seminal contribution, according to Epstein, is his concept of the “facilitating environment” provided by an “attuned” mother for her child. This allows the child to stay in touch with his subjectivity rather than being cut off from it and needing to create a false self to survive psychologically.

Now let’s apply these ideas to trading.

There are two main schools of trading, Value Investing and Technical Analysis. Unfortunately, out of a need for an unattainable certainty, most traders choose one school and become dogmatic about its principles. Value Investing and Technical Analysis are essentially the two religions of trading. Great traders, however, integrate the insights of both.

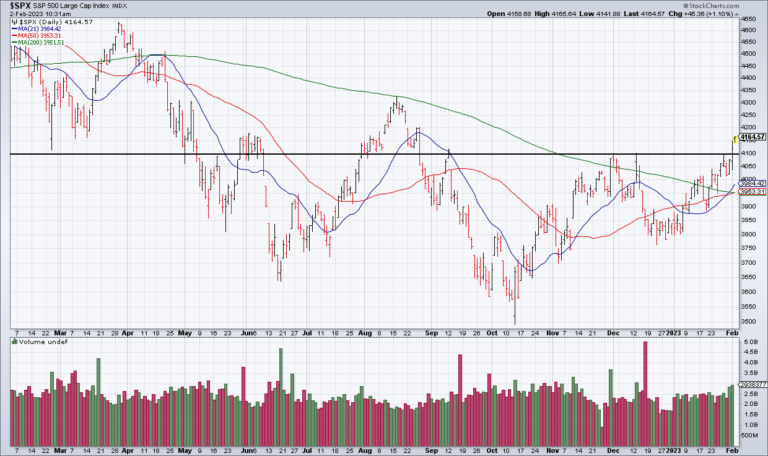

Value investors look for a difference between the market price and the intrinsic value of a security. If a security is trading for $50 but is worth $75 in the value investor’s estimation, it’s a buy. The problem with value investing is that just because the value investor believes the security is worth $75, even if he is “right”, doesn’t mean the market will immediately reprice it to his opinion. The market has a mind of its own and doesn’t care what anyone thinks. Therefore, value investors are exposed to the risk of becoming impulsively stubborn. They hold the position as the market moves against them or even add to it. Put another way, they lack flexibility and attunement to the market.

Sometimes this is the right thing to do if the value investor is convinced that he knows better than the market and the market will eventually come around. As the great Wayne Gretzsky said, “I skate to where the puck is going, not where it’s been”. But if it’s coming from a place of impulsive stubbornness, the value investor frequently gets “run over” by the market. In other words, the value investor is so invested in his own opinion that he is can’t listen to the message of the market – and, like I said above, the market has a mind of its own and doesn’t care what anyone thinks. He may be “right” but he’s going to lose money.

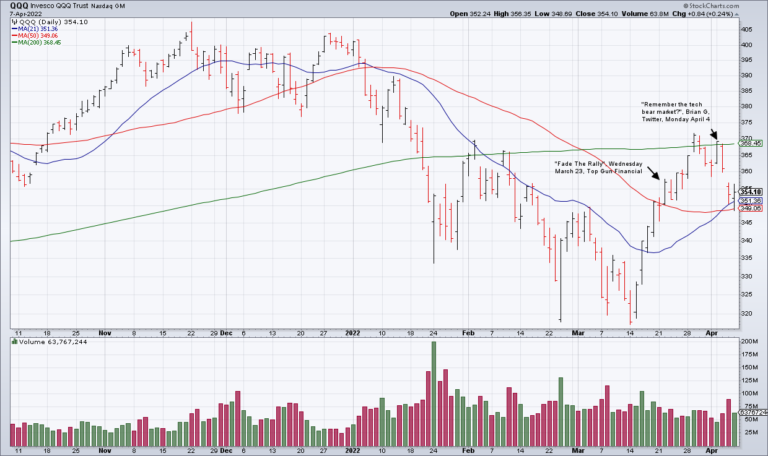

Technical analysts believe that “price is truth”. They are quite attuned to the market and outperform in strongly trending markets but have no independent conviction about where price “should” go based on fundamentals. As a result, technicians are often “whipsawed” by the market as it zigs and zags on a day to day basis, confusing them as to its ultimate direction. They suffer from being overly flexible and ignore Peter Lynch’s idea that you can’t catch every wiggle but that “earnings waggle the wiggles”.

What to do? A synthesis of Value Investing and Technical Analysis combined with Epstein’s two psychological concepts helps the great investor balance stubbornness and flexibility. Investing, like therapy, is an art, not a science, and so there are no hard and fast rules for this. The best the great trader can do is to be aware of his impulses to be overly stubborn or overly flexible and therefore make decisions from a place of conscious reflection and centeredness, not impulsivity.

When he observes himself feeling stubborn or flexible, he needs to step back and gain some psychological distance from his impulses. Sometimes the right decision will be to be flexible and adjust based on market action that is moving against him. Other times it will be right to dig in one’s heels and be stubborn. The key is to act from what in Buddhism is termed Right Intention. That is, to be aware of the impulses that are driving one, get psychological distance from them, and act consciously and creatively. This by no means guarantees that one will always be right but it is the Zen of Trading.