Markets, Uncertainty, Forecasting

WARNING: This blog is a philosophical exploration of markets and has nothing to say about what is going on in markets right now. For those of you who are not interested in that sort of thing, I suggest you skip it. For those of you who are, I hope it doesn’t give you a headache.

*****

On my flight yesterday (Tuesday) from San Jose to San Diego en route to Coronado for a short vacation, I reread the first chapter of Alex J. Pollock’s book Finance and Philosophy: Why We’re Always Surprised (2018) titled “Fundamental Uncertainty”. Being a Philosophy major – in fact I was a Philosophy Phd student at UC – Davis from 2003 through 2005 and have a M.A. in Philosophy in addition to my B.A. from UC – San Diego – I can’t help but be drawn to Pollock’s book and the questions it raises.

In “Fundamental Uncertainty” Pollock starts to detail his answer to the subtitle of his book: “Why We’re Always Surprised”. Market participants – investors, economists, regulators, etc… – always seem to be caught offguard when financial crises emerge. Frequently, the vast majority of investors are bullish at the exact top. Quant models frequently work well until an outlying event not accounted for by the model occurs and the portfolio blows up. For example, the “Quant Quake” of August 6, 2007 or the blow up of Long Term Capital Management. Why?

Pollock argues that it’s not because they’re stupid but because of “fundamental uncertainty”. Let’s start to unpack that concept. Citing the economist Frank Knight and his 1921 book Risk, Uncertainty, Profit, Pollock makes a distinction between risk and uncertainty. In risk, you don’t know what’s going to happen but you know the odds. For example, in poker when you have a flush draw on the flop – two cards of the same suit in your hand and two on the flop – the chance of completing your flush is 38.7%. That’s because there are 47 cards left in the deck for the turn and 9 of them are of the suit you need. If you miss on the turn, there are 46 cards left in the deck for the river and 9 of them are your suit. (9/47) + (9/46) = 38.7%. That’s risk. In uncertainty, however, Pollock argues that you can’t even know the odds and that that is “ineradicable”.

But there is an ambiguity in Pollock’s concept of “fundamental uncertainty”. Is Pollock saying that we can’t know what will happen in the future with certainty or that we can’t know anything at all about the future? This is the important question as nobody believes the former but if the latter is true all forecasting, including investing which is a form of forecasting, is hopeless. For example, Warren Buffett would just be a statistical fluke. Pollock doesn’t seem to recognize that this is the crucial distinction. Of course there is ineradicable uncertainty about the future. But can we know anything about it that will give us an edge? If not, we’re just blindfolded monkeys throwing darts.

Indeed, Pollock’s arguments imply that we can know nothing about the future. Pollock argues that the complexity and reflexivity of markets and economic life – and all social behavior by extension – is such that even rational reconstructions of the past are impossible:

Problems of systems of dense, recursive interactions not only baffle economic and financial predictions, but also generate competing interpretations of economic history. Theories of what caused the housing bubble…. and the ensuing crisis continue to be debated eight years after the end of the crisis.

The problem is no less evident when considering competing theories about long past economic events. Causes and dynamics of The Great Depression of eight decades ago also continue to be debated. What caused what is not that clear, even after decades of competing studies (p. 16-7).

As I said before, if we can have no rational basis for making one forecast over another or accepting one historical interpretation over anothing, then investing – and indeed all history and social science – is hopeless.

But Pollock goes too far. While he is right to start his book on finance and philosophy by emphasizing the complexity (i.e. large number of variables effecting outcomes), reflexivity (i.e. interaction among the variables) and uncertainty (i.e. not everything can be quantified) involved in financial markets, he fails to recognize that we can know things that can help us make good forecasts and that there are better and worse interpretations of the past. For example, through long experience Buffett learned that “it is better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price”. That is, Buffett discovered the crucial importance of quality for stocks that can compound over long periods of return and produce exceptional returns. His track record is not a fluke but based on something he learned about succesful businesses. Similarly, anyone who reads Gibbons The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire or John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Great Crash can’t help but think that they have identified some of the key factors in what they explain, even if they can’t provide a complete explanation.

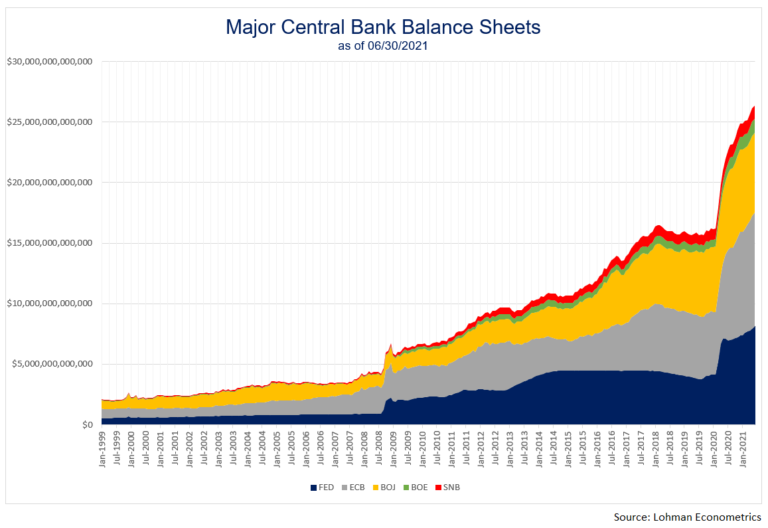

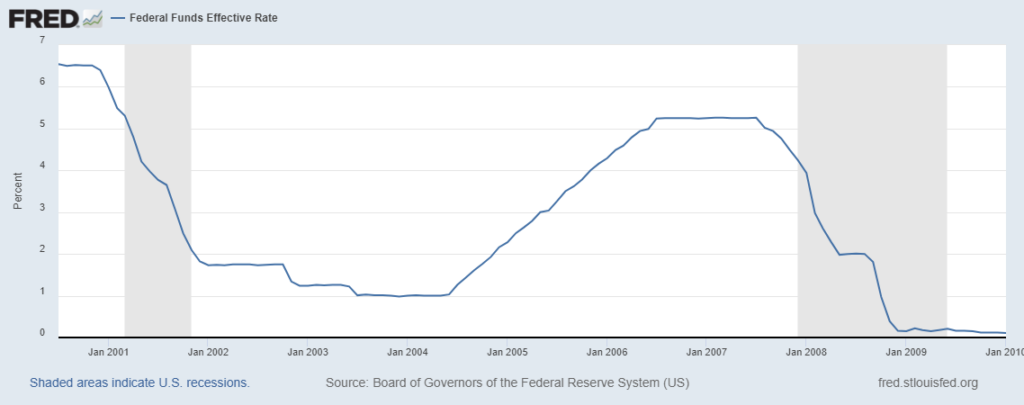

In fact, I dropped out of Philosophy graduate school at the end of 2005 to start Top Gun because I was sure that the housing market was going to collapse and infect the entire economy. Having studied the Austrian Economist Ludwig von Mises, I understood what Greenspan had wreaked by keeping interest rates too low for too long – and what the ultimate consequences would be. I wasn’t the only one either. And things played out exactly as I forecasted they would. Was this complete luck as Pollock would have it? (To be fair, Pollock proceeds in his book as if we can know some things about what is likely to happen in the future and therefore have an investment edge but his argument in chapter 1 tends toward negating that assumption).

While Pollock is right to emphasize the complexity, reflexivity and uncertainty involved in financial markets, he fails to understand that some human beings can understand enough of what’s going on in the present to make forecasts about the future performance of financial markets that result in excess returns. (In addition, some historians are able to glean real insights into why what happened in the past happened the way it did). Just the other day I was messaging one of my old Philosophy buddies from UC – San Diego about how “endlessly fascinating” markets are. While Pollock has gone some way to showing why this is so, the implication of his argument is that we can know nothing at all about the future. This whole blog – indeed my whole career in investing – is really an exploration and search for how this might be done. Hopefully I have not completely wasted my – and your – time.